Nearly 55 years after the Fair Housing Act was signed into law, Black homeownership still lags behind white homeownership — by a lot.

The legislation enacted in April 1968 was meant to address discrimination in the selling, financing or renting of any home, but the numbers show we still have a long way to go. By some measures, the Fair Housing Act has resulted in no progress.

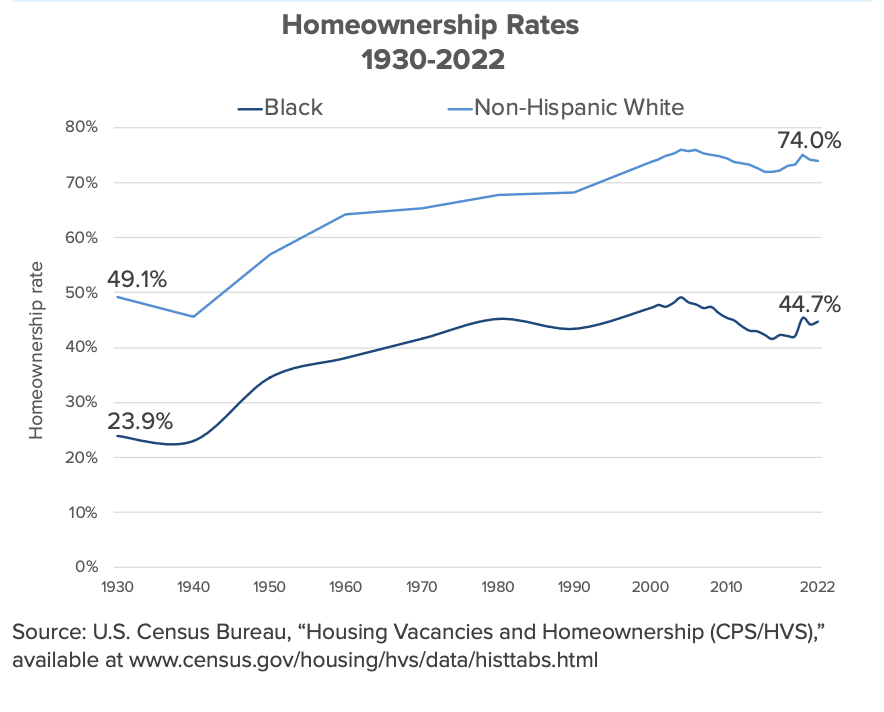

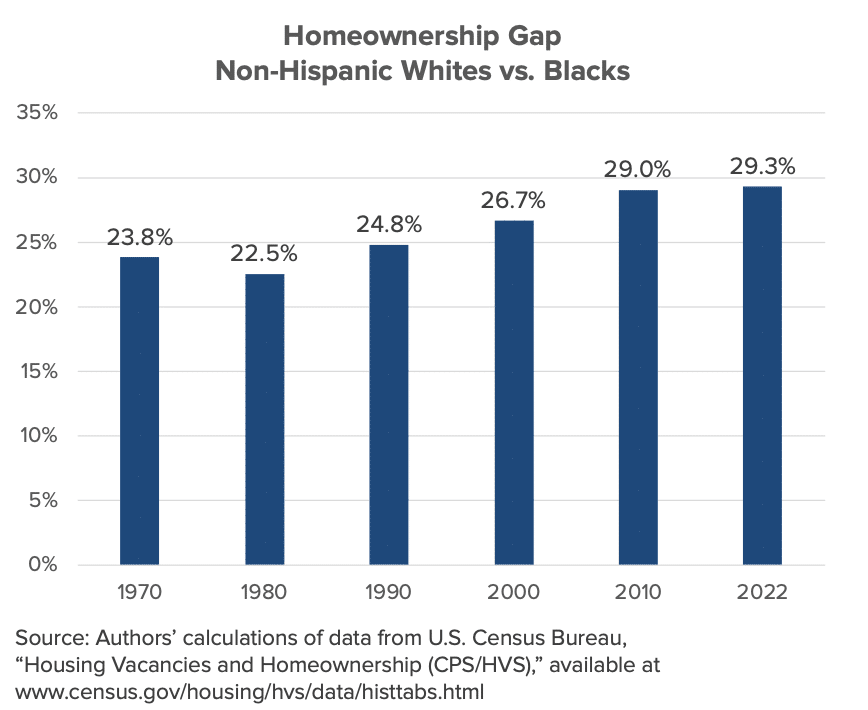

Just 45.3% of Black households owned their own homes in 2022, according to the National Association of Real Estate Brokers (NAREB), compared to 74.6% of white households. That 29-point percentage gap is larger than the 27-point gap in 1960, before the Fair Housing Act was passed.

The National Association of Real Estate Brokers’ (NAREB) annual State of Housing in Black America (SHIBA) report further illustrates the discrepancy. NAREB President Lydia Pope’s introduction to the report offers some historical context for today’s dwindling numbers. The year 2004 marked the highest rate of Black homeownership: just under 50%. But when the housing market collapsed in 2008, Black people were affected disproportionately by predatory lending. And 15 years on, that homeowning demographic has not fully recovered.

As Pope explains, NAREB normally uses 2004 as the benchmark against which to measure progress. With the rate of Black homeownership so low — mirroring numbers from the 1960s — that convention has been updated. This year, the SHIBA report uses 2008 as its base year to better understand the lasting effects of the foreclosure crisis.

Data from the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act

Blacks make up 12% of the U.S. population, and in 2021 they made up just 7% of overall mortgage originations for the third year in a row. However, the number of loan applications is rising overall. And non-white groups are making up a greater share, while the number of white applicants remains “virtually stagnant,” according to the Home Mortgage Disclosure data.

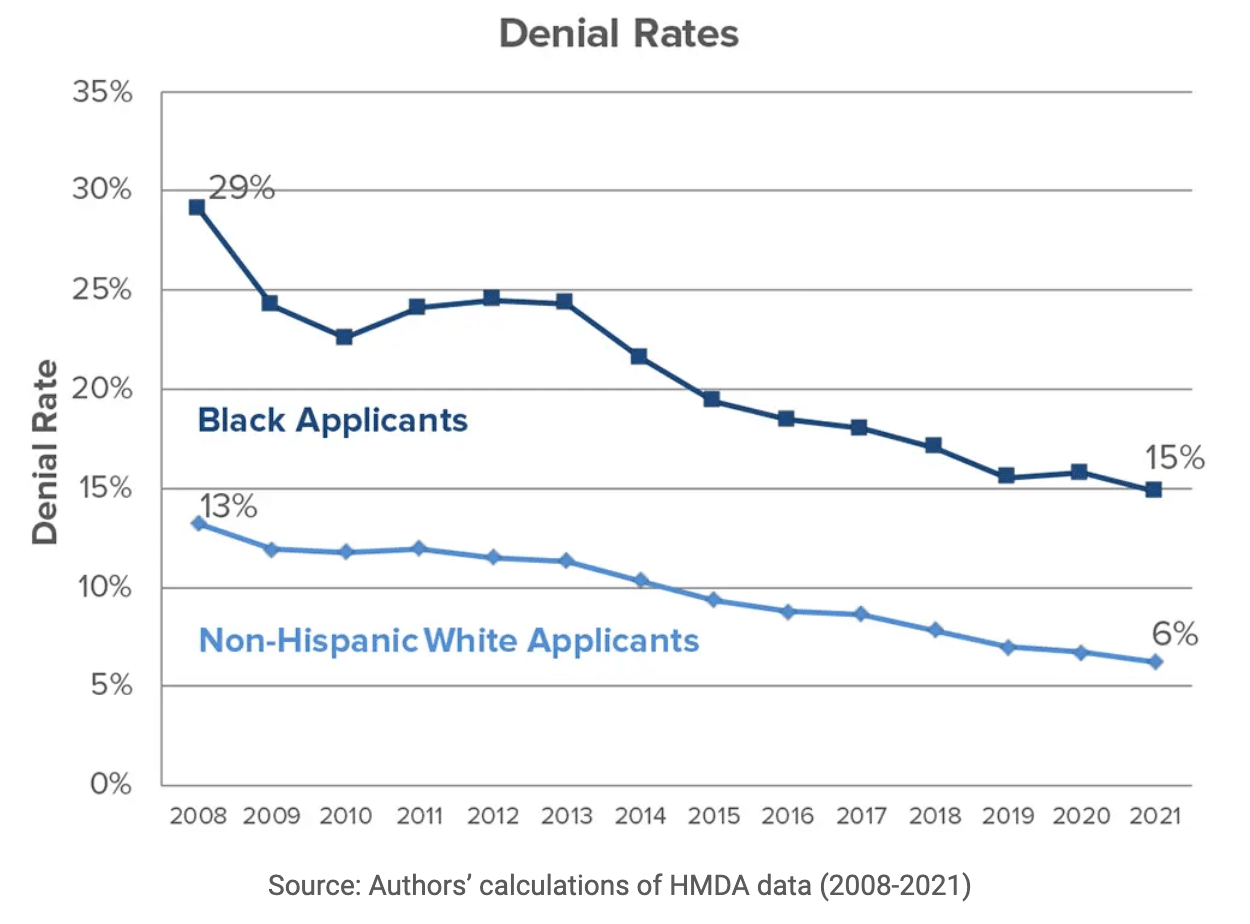

As a result, the number of loan applications from Black people rose by 13%, year over year, in 2021, while the number of originations rose by 15%. However, Black applicants continued to experience higher loan denial rates than white applicants. In 2008, 29% of Black applicants were rejected by independent mortgage companies, compared to 13% of white applicants. And though denials went down overall, in 2021, the racial gap continued. The percentage of Black applicants denied by independent mortgage companies that year was 15%, nearly triple the 6% denial rate of white applicants.

via NAREB’s 2022 SHIBA report

At banks, the rate of rejection remains higher. Black loan applicants had a 20% denial rate at banks, compared to an 8% denial rate for white applicants. Denial rates were also high for Black applicants in majority-minority neighborhoods (at 16%), compared to white applicants in similar neighborhoods (at 7%). Additionally, Black homebuyers are more likely to receive high-cost loans: 14% compared to 5% of white recipients.

In turn, Black homeownership — and therefore Black wealth — is hindered.

Black homeownership statistics

The 2021 Survey of Income and Program Participation, as cited by NAREB, indicates that in 2020, the median white family held 12 times the amount of wealth of the median Black family. For perspective, that’s an estimated net worth of $18,430 for the median Black household compared to $217,500 for the median white household — a stark difference. But how did we get here?

According to NAREB, much of the answer lies in barriers to homeownership. For most Americans, homeownership remains the most direct means to accumulating wealth. And as the SHIBA report points out, this is especially true for people of color. In 2020, home equity represented 67% of a Black households’ net worth — 10% higher than the net worth share for white households. Thus, removing obstacles to Black homeownership is imperative to securing economic security for families of color.

Citing the U.S. Census Bureau, the SHIBA report shows that during the first quarter of 2022, the Black homeownership rate was 44.7%, down slightly from 2020 and close to the rate from 1968, when the Fair Housing Act was first passed.

via NAREB’s 2022 SHIBA report

via NAREB’s 2022 SHIBA report

Avenues for Black homebuyers to obtain loans

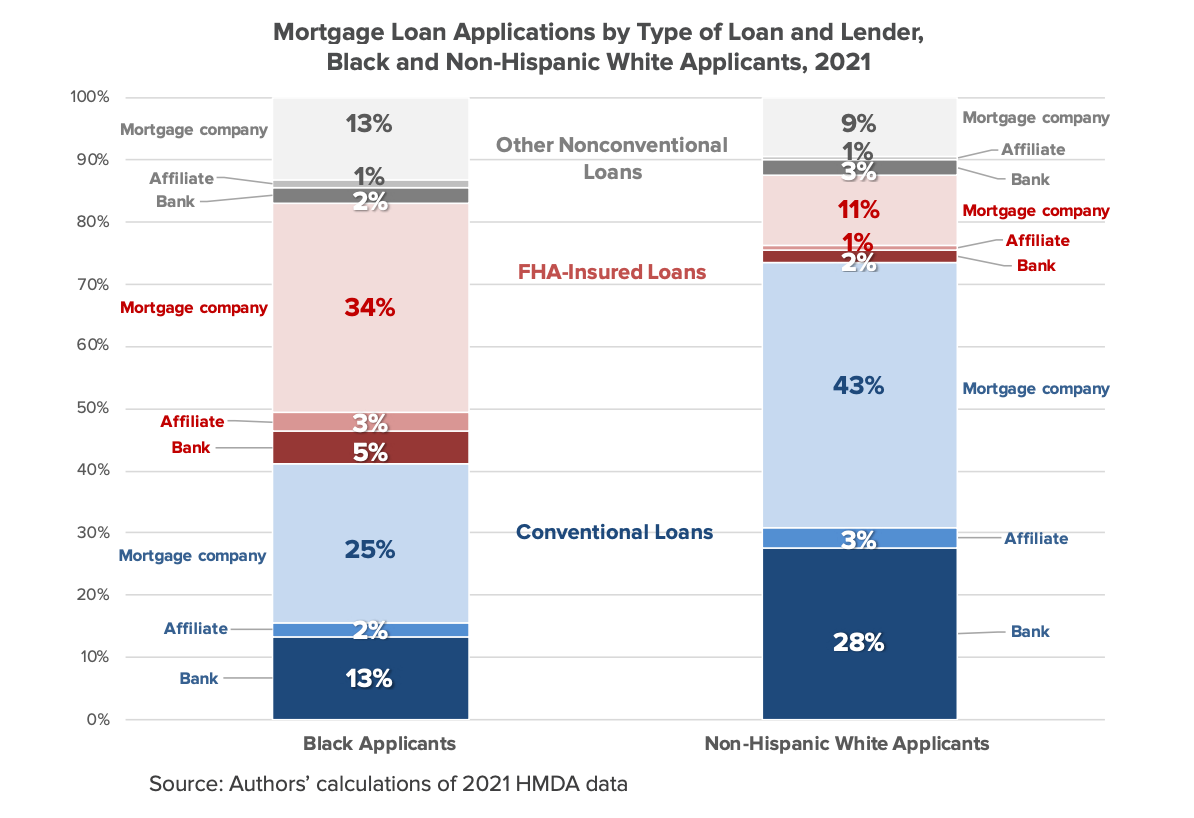

As anyone in the industry knows, during the past decade, mortgage lending has shifted from traditional banks to independent mortgage companies. These non-bank institutions are not subject to the same regulatory oversight and often include technology, or fintech, as an alternate lending channel. It’s a growing field in our digital age, further popularized by the decline of bank lending after the 2008 financial crisis.

Although people of all races seek loans predominantly from non-bank institutions, 72% of Black applicants opted to seek a mortgage company loan, compared to 63% of white applicants. These institutions are typically more flexible when underwriting because they operate without bank regulation. However, NAREB points out that with higher rates and higher fees, the end result can be a high-cost loan — contributing, at least in part, to the larger share of high-cost loans experienced by Black borrowers.

via NAREB’s 2022 SHIBA report

What now?

As NAREB’s SHIBA report illustrates, year after year, Blacks continue to struggle to become homeowners compared to whites. But looking back, the rate of Black homeownership seen in 2004 — when nearly half of Black households owned their own home — “speaks to the tenacity of Black America and its willingness to continue to struggle for equality in this nation.”

It’s also important to remember that white households did not achieve their own high homeownership rate overnight. It took substantial federal finance assistance, stretching back to the 1930s.

Now, NAREB suggests similar recommendations to improve the rates of Black homeownership. They include eliminating loan-level pricing, removing fees associated with down payment assistance, recalculating the way student loan debt is treated during the underwriting process, eliminating appraisal bias and, overall, restructuring the housing finance system to create programs that are new and innovative.

“The current system was also not designed to meet the needs of households whose incomes and credit profiles differ from those of white households,” the report concludes. As such, addressing the needs of Black households will require fixing the system itself.